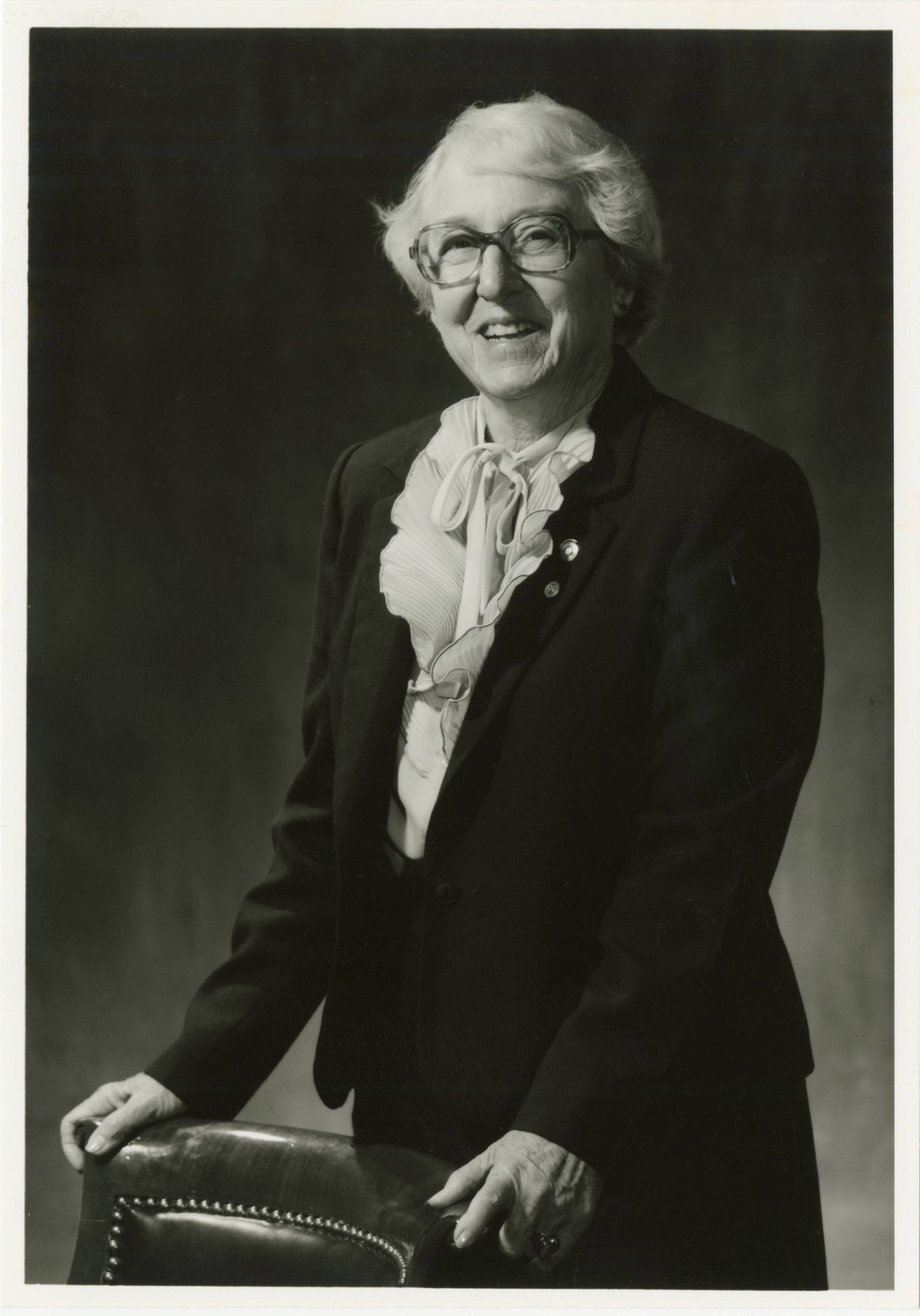

Ruth Bain

Ruth M. Bain

Biography

Dr. Ruth Bain (1919–2011) was born in Centerville, Texas. She did her undergraduate study at the Texas State College for Women. Bain attended the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston and graduated in 1942. After interning St. Louis City Hospital in Missouri, she completed a residency at Brackenridge Hospital in Austin. In 1951, she entered private practice in Austin where she worked for thirty-nine years.

Bain also actively participated in the Travis County Medical Society. She served as its secretary-treasurer from 1958–61, and in 1962 was elected its president—the first woman to be elected to that office. Bain also served as past president of the local chapter of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians (1982–83). She served as a member of the board of directors of the Travis Country Medical Society Foundation and as a member of the District Review Committee of the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners. This last office was an appointment by Governor Dolph Briscoe.

Part of the Texas 150 Oral History Project

Bain describes how the medical field and opportunities for female doctors have changed over the span of her career, especially in Austin, Texas. Bain briefly discusses growing up in Centerville, attending college at the Texas State College for Women, and going to medical school at the University Medical Branch in Galveston. Beyond talking about being a woman in medical school, Bain shares her experiences working at Brackenridge Hospital and starting her private practice in Austin. She later recalls her participation in a number of medical societies, including the Travis County Medical Society and the Texas Medical Association, as well as the state of healthcare and insurance in the United States.

Audio File Access

Full audio is available for this interview. Reading Room access only.

Transcript (PDF)

Transcript

Interview with Dr. Ruth M. Bain

Interviewer: Cathy Bachik

Transcriber: Cathy Bachik

Date of Interview: October 2, 1986

Location: Dr. Bain’s Office, 4 Medical Arts Square, Austin, TX

Begin Tape 1, Side 1

Cathy Bachik: This is Thursday, October 2, 1986, and I am Cathy Bachik. I am in the office of Dr. Ruth Bain in Austin, Texas. Dr. Bain has agreed to spend time with me to discuss how the medical field has changed over the years, including opportunities for women physicians.

Dr. Bain, if you could give me some information about your family and where you are from.

Ruth Bain: Well, I was reared in a very small town, Centerville, Texas, which is in Leon County. It is about halfway between Houston and Dallas. I am the seventh of nine children, and my parents have been deceased for an extended period. I went from high school to what then was Texas State College for Women and now is TWU [Texas Women’s University, Denton, Texas], and took my bachelor’s degree from there and then went to medical school at the University Medical Branch in Galveston. Then I had an internship in St. Louis and then residency for eighteen months here at Brackenridge. That’s how I happen to be in Austin, you know, like most people when you get to Austin and you stay a little while, you don’t want to leave.

Bachik: Had you always planned on returning to Texas, after you finished?

Bain: I’m sure I planned to return to Texas. I really didn’t have any long-range plan. I, like most people coming out of medical school, had some dependents, financial obligations, and so I went on a salary basis at the University Health Center for three years and got some of those obligations behind me, then went into practice here in town.

Bachik: When you went to medical schools, were there very many women in the program?

Bain: Well, interestingly, we had one of the larger classes. We were eight out of a hundred physicians, or a hundred accepted at that time. We lost one or two, but we picked up one or two that had dropped back or had to leave school for illness or some such thing. So we graduated eight out of eighty. I would guess that most of the classes at that time had three or five, something like that. So we were one of the larger classes of women at that time. That’s been one of the significant changes. As you may know, the medical school classes, not just in Texas, but all over the nation now run in the 30, 35% range of women.

Bachik: When you went to the medical school, did they provide housing?

Bain: Yes, as a matter of fact, there was a building called University Hall that had been dedicated for housing for women physicians, or women students at the medical school, that was an old building. It is long since and gone. I think that most of the students now are in apartments and that sort of thing. There is no provided housing. This, of course, was at a fee, but it still was right close to the campus, right across the street from the main hospital, very convenient and very adequate. [Referring to University Hall]

Bachik: Was there any difficulty in trying to get accepted in a residency program, being a woman?

Bain: I didn’t find it so. I really have been asked this question so many times because there is the assumption by the younger women that it must have been terribly difficult at that time. I think those of us who went into medicine at that time were very much aware that we were going into an area that women were of the minority, and I think we were all very dedicated and determined to succeed at being physicians. I am almost hesitant to say this, but I think that my perception of young women today is that sometime they make their own problems by looking for problems. We didn’t look for things to fight about. We were too busy going to medical school.

I think that the chip on the shoulder is not a good way to approach anything. If you want to find problems, they’re out there, and you can find them. But, I really think that I was so determined that I was willing to be the brut of a joke every now and then and let it go over my head like water off a duck’s back because I was not going to be deviated from my goal by pettiness.

Bachik: You must not have encountered many problems when you went into your private practice.

Bain: I really didn’t. I’d either been extremely lucky or there are not as many alligators out there as had been thought to be. How I got started in practice was interesting. I was on the staff, as I said, at the University Health Center, and one afternoon a male physician, who was also on at the University Health Center, came in, propped his feet on my desk, and said, “Ruth, you don’t want to do this the rest of your life, do you?” and I said, “No, what did you have in mind?” And he said, “Well, I think we ought to get our feet wet.”

So, to make a long story short, he had already been looking for an office. He had a wife and two children, and he couldn’t handle it by himself, so we wound up renting an office that was big enough for one physician, with one desk, and he had the drawers on one side, and I had the drawers on the other. For two years, we went on half-time at the university, and one of us went to the office in the morning and the other one went to the University Health Center. At noon, we did fruit basket turnover. By the end of two years, he decided he wanted to take some further training. By that time, the two practices were big enough to sustain me, so I took over the practice, and he went back for more training.

A few years later, a physician, a male physician here in town approached me and said, “Ruth, I’ve got a lot down here on Seventeenth Street, and I’d like to put a building up for two doctors. Would you be interested in going into a building program with me?” We did, built the building, practiced in a two-doctor office building down there for, oh fifteen to eighteen years. See, I don’t relate to those problems.

I was on the staff here at Brackenridge as a resident during the war years. There was a shortage of physicians. By the time I came out of training, I knew every doctor in town, and they knew me. So the relationship I had established by doing the job that I had done there just served me in good stead in getting started in the medical community.

Bachik: When you went into practice, did most physicians then go into general practice or was it specialties?

Bain: That’s a real difficult question. Certainly, there has been a change. I guess at the time that I went into medical school, there was probably a majority of primary care/family practice. The old term is general practice, family practice now, is a recognized specialty with three years of required training after medical school. Actually, our training for family practice for board certification now is the same that it is for pediatricians, for general internal medicine, and a lot of the other specialties.

At the time I came out, I guess, certainly in our part of the country, the large majority were family practice or general practice. Then there was this great flourishing of specialty after World War II to the extreme, we went from one way to the other as the pendulum is apt to swing. Now, in the last ten years particularly, there has been a swing back toward the family practice area. There is an increasing number of people coming out of medical school going into family practice. They now have the prescribed programs for the three-year residencies as we have here in Austin for family practice. So, most of your people who are going into family practice now are board certified, have had significant training, usually three years, and are in the same category, simply a broader specialty than the others.

Bachik: Did you go to the same length of school as they do now?

Bain: Well, the period of time in medical school has not changed. No, that’s the same for everybody regardless of what you are going to do. You go through medical school and get your MD degree, all specialization regardless of which direction is after medical school. So, say a general surgeon and brain surgeon goes through medical school, then their residency is in their special field.

Bachik: Did anyone else in your family ever go into medicine?

Bain: No, they did not, and have not. I’ve been asked again on many occasions why I chose it, and I really don’t have a very good answer for it. I think it may be that I was just hard-headed, and when I said something about wanting to be a doctor and people’s mouth dropped open, I think it just made me a little more determined. (Laughs)

Bachik: When do you think that you finally really decided what you wanted to do?

Bain: I really can’t remember seriously wanting to do anything else. Certainly by the time I finished high school, I was very determined. I guess one of the things that stands out of most in my memory in that regard, and I think has been an influence in my career and thinking, [is that] my mother was a very wise woman. Not highly educated but reared nine children. My father died when I was eleven, so there were four of us in high school or younger when my father died. My mother carried a great deal of responsibility well.

I remember very vividly, sitting on the front porch shelling peas in the summer before I was to go off to college. My mother said, “Ruth, you have this idea that you want to be a doctor. I don’t know what that means. I have never seen a woman doctor, and I assume that whatever your life will be like, it will be different from any of the rest of the children.” She said, “You know our resources are limited.” She called my younger brothers and sister by name and said, “You know they have to be educated, too. And, I don’t know how long I can support you in that endeavor.” But she said, “I think that you have great determination, and in this great country of ours, those people who are determined and will work at it, the doors will be open unto you.” And there was never a truer statement made.

I have since seen young women who came out of backgrounds with families who had greater economic resources but whose families for some reason didn’t support them to that degree. It made their road harder. So, I think there is no doubt that the fact that she indicated a willingness to help to the degree that she could, but more than that, that little push that you need every once in a while in life that says you can do if it you try.

I think that is extremely important. I was as naïve as she was uninformed. I’d never seen a woman physician at that stage in my life. But, I have looked back on that on many occasions and thought what a strengthening and what a positive effort it was for an individual, without information, but just with optimism, with the feeling, just as she said, in this great country of ours, if you want to you can do it. If you want to badly enough.

Bachik: Did you work in addition, when you were going to school, to get the support that you needed?

Bain: The only semester that I did not work throughout college and medical school was my first year in medical school. I have washed glassware, mix agar, put cats to sleep. (Laughs) Just about everything you can do.

Interestingly, my first year in medical school, by the time I had completed my pre-med work and was still determined, my family began to get more involved with wanting to help. There was a little fortunate financial situation there that some oil lease money for land comes into the hopper, so my family sort of had a conflab. They had heard such terrible things about how many people did not make it through the first year in medical school, so they said, This year, you don’t work. We will see you through the freshman year. So, that’s the only year that I didn’t work during my entire college and medical school career.

The last year I was in medical school, I lived at the state psychiatric hospital in Galveston and was called what they called an “extern.” I got room, board, and laundry for that, so that was a big item. For doing that, we were on call. We were all senior students, four of us in the building, and we alternated call and got up at night if somebody became disturbed in the psychiatric unit. We did intake histories from families on patients coming in. That was my senior medical school job.

Bachik: I know that you are the past president of the Texas Medical Association, and I believe there was one other woman who was president.

Bain: Yes.

Bachik: What year were you president?

Bain: ’82–83.

Bachik: Did you decide to run?

Bain: (Smiling) That’s another one of those interesting developments. Being president of TMA was never on my agenda. I seemed to have been fortunate at being at the right place at the right time. I have been active in organizations since the beginning. As I indicated a while ago, by the time I finished my training, all the doctors that were here—there were much fewer doctors then than there are now in Austin—knew me, and I went into practice in ’50 or ‘51.

In ’57, I was elected secretary of the Travis County Medical Society. I went through the ranks there and was president of the Travis County Medical Society twenty years before I was president of TMA, (laughs) in ’62–63. I sort of had assumed I had done my dues when I got through with that, was going ahead about my affairs, and I was called one night while I was attending a family practice meeting by one of the specialists in town. He said, “Ruth, there is vacancy at the state level on the Board of Councilors at TMA.” The Board of Councilors is the ethical body, policy-making body of TMA, and they also serve as an appeal mechanism for doctors who have been disciplined on the county level [and] can appeal to the state level. [He] said, “We would like to put your name up for vice-councilor from this district.” I was not really aware of all this entailed, but I said to the doctor, “If you all feel that I have some expertise that can be used on that level, I’ll be glad to do what I can.” So, I went on the Board of Councilors, and I’m the only woman who has ever served on the Board of Councilors at TMA. (Laughs)

After I had been on the Board of Councilors, I think I was on the board for ten years, probably. Anyway, toward the end of that time, I was visited by a group of physicians from here in town who came to see me one day and said, We think you ought to let us put you up for president of TMA. I was shocked and flattered. I said, “Gee, I’m sorry but I can’t afford it, the time or money. I really don’t feel that I can do this.” The next year they came back. (Laughs)

By that time, of course, I had had time to think about it a little bit, and then another physician announced the rumor was out that I was going to run, and a physician from Dallas called and said that he would like to run, and would it be inconvenient to my schedule to run the following year. To make a long story short, I agreed to that, and I didn’t have an opponent.

Bachik: Did you enjoy being the president of TMA?

Bain: It was a tremendous experience. In the three years that I was president-elect, president, and on the board as a past-president, executive committee, I probably learned more than I had learned since medical school but in an entirely different arena. This was in the socioeconomics’ arena and in the political arena of how medicine is being affected. I have been heard to say on occasion that I learned more about that than I really wanted to know. (Laughs)

Bachik: Were you also the president of the family physician—?

Bain: I was president of the local chapter, not the state, several years ago.

Bachik: Can you give me a little bit of information of how medicine, just in general, has changed since you went into practice?

Bain: Well, it is almost unbelievable when you look back. You know, when you are going through a thing and you keep up with the changes as they are occurring, you don’t think so much about it. But, the progress in medicine, particularly after World War II, it is really unbelievable.

When I graduated from medical school, the only medications effective that we had to treat infections with were sulfa, that had come in 1937, and penicillin in 1942. That’s all we had, and we didn’t have a lot of that. And when I look at the array of antibiotics that are on the horizon or available to us today, when I look at heart surgery and all of the technical developments, when you look at mammography and MRIs, this new system that has recently come out in the last year or two that is primarily of help in looking at the brain, and as for CAT scans, at the time I started out, that was not an imaginable thing.

The strides that have been made in diagnosis and treatment, perhaps even more than that, the disappearance of things from the medical scene that use to kill a lot a people. We don’t have a lot of people who die of infection at the present time unless they are complicating other debilitating disease.

Polio. When I look back and I remember when the summer came, the level of anxiety in the young parent population increased. Everybody had a horrible fear, rightfully so, of polio. We don’t even see polio anymore. The advent of diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough vaccine, and a polio vaccine, has done more to eliminate, not just death in children, but complications of those things that use to lead to lifetimes of deafness, of paralysis with polio—we don’t see them anymore. The young people who are facing stress in other areas now are not aware of these tremendous changes that just really are fabulous.

Bachik: I know that suicide and that type of thing is on the rise. Were there a lot of people committing suicide?

Bain: I don’t suppose there has ever been a time when people didn’t commit suicide. A lot of what we hear about suicide now is because our media is so much greater. Suicide used to occur, but it was not broadcast. The families reacted as families will in a protective mechanism or way. So, every death that occurred didn’t have to be investigated back in those days by the coroner or that sort of thing. I think that certainly there were suicides. I think there has been an increase with two things: with the increase in longevity and in the number of people who survive. See, when you just increase the population by tens of thousands, if you multiply and same number of people with suicide, you get a higher number. And, if it is on the front page of the paper, it seems like more.

Nevertheless, there was an article in a medical journal four or five years ago that impressed me tremendously, and I think it indicates a significant change. What it did was take the age and numbers of people and the causes of death. In the United States, this is almost like a rectangle. I mean there are a few deaths in early childhood, relatively few in the teenage years, except by accidents, and you get up into the older age group then, and people primarily now die of three things: cancer, heart disease, and stroke. If at the age of sixty, seventy, or eighty, you save one of those people from one of those, they’re going to die of one of the others. (Laughs)

On a percentage basis, when we eliminate measles, whooping cough, polio, pneumonia, all of the infectious diseases, when we started immunizing for tetanus after World War II, you don’t see tetanus anymore. When you eliminate all those things, it just almost goes up perpendicular. [Referring to the rectangle] Where you compare that with an undeveloped country, like India, and theirs is like a triangle. They have a huge base of birth because they have no birth control, and then the death rate is almost triangular to a peak, because they’re still losing all those people from all the things we don’t lose people from anymore. It is interesting.

Bachik: Were there many insurance companies then that people filed claims with?

Bain: Insurance that was available then was true insurance. By that, I mean it was insurance for catastrophe. Then certainly Blue Cross/Blue Shield came into the force some time, I don’t know the years on that, and started covering more general things. But, back in the days when I first began, people had insurance for catastrophe, and that was about it. They met their own individual medical needs, and that’s been one of the big changes, which has been good in some ways and now is a significant threat to the system.

The present time, the government and employers pay for close to 70%, I’ve heard varying statistics, of the costs of health care. We have removed the individual from the responsibility to a large degree, and that has been one of the big factors in the increasing cost of health care. When you remove the individual from responsibility from paying for their care, you remove any restraints, so that the demand goes up.

Rand Corporation did a survey in 1980 that found that there was a 60% increase in demand of health care with first dollar or close to first dollar coverage. That may be good in some ways in that people may be seen earlier and get care more appropriately, but it also adds a tremendous burden to the system. The increase in demand has been a real problem and contributes to our trying to cope with health care costs on the national level.

Bachik: How much do you think, even percentage-wise, has been an increase of lawsuits since you entered?

Bain: Oh, phenomenal—tenfold. I don’t remember even hearing about lawsuits in relation to doctors until the last, maybe, fifteen years. We have, and this doesn’t apply just to doctors it applies to everything; we’ve just become a much more litigious society. There was a time when people accepted misfortunes, bad luck, whatever. Now, there is no such acceptance. Somebody did something wrong, and somebody should pay for it. So, it is a totally different attitude, which I think is unfortunate. If you just read the papers about people that sue each other and what they sue each other about, it gets almost to the ridiculous. But that it’s an attitudinal thing in society as a whole.

My great concern about the lawsuit situation, as far as professional liability and physicians is concerned, is that it has become such a tremendous problem now that it is affecting access to care and quality of care. I am convinced that we are going to see deaths of young women in child birth because they are unable to have their needs met because of the cost of liability insurance.

I did obstetrics as a part of my family practice for the first twenty-plus years. I did not stop because of liability problems, but a large percentage of my family practitioners now do not deliver babies because they cannot afford to deliver babies and pay the cost of liability insurance. A lot of the small towns, and I think that’s where the problem is going to be with the young women, a lot of the small towns do not have obstetrical care available. Those people are having to go forty, fifty, sixty miles away. In a true emergency, that can be a problem. The large, large majority of obstetrical cases, of course, are normal deliveries and without problems. But when emergencies or complications do occur, they frequently occur rapidly, and then need immediate attention. I don’t think the public is aware of this.

Just here in Austin, Texas, last year, in order to be on the staff of one of the local hospitals, you had to produce evidence that you were carrying a minimum of $500,000 coverage in professional liability. I had never carried that much in my professional career.

The reason for that is that when something happens in a hospital setting and somebody sues, they sue everybody. They sue the hospital, the doctor in charge, the consultants, the anesthesiologist if an anesthetic was administered, perhaps somebody in x-ray—it is a blanket thing. The current situation is that payment, if the patient wins a suit and gets damages, the damages are not parceled out according to your negligence or according to your responsibility in the case, it is according to who has the biggest policy. There is not fairness as far as physicians are concerned. If I had just happened to be the one who had the highest policy but had almost nothing to do with the case, mine might be the one that would be hit the hardest.

That’s just one of the things. There are many, many—it is a multifaceted problem, and I think the fact that it has spilled over so broadly in all that you are reading now in the paper where people on boards of directors of banks or insurance companies, so forth, can’t get insurance. I have a young niece who’s an attorney, and the attorneys are now having problems getting professional liability insurance. So maybe that the thing is being put upon the attorneys we may begin to get some relief. (Laughs) But, it’s a broad-based thing. It’s pervasive of society.

The one thing that I did want to mention that I think people are really unaware of is, and they talk about the cost of health care, if a physician pays $20,000–$30,000 a year for liability insurance, the only way they can pay for that is to increase their fees to take it from patients. That’s the only way they can do it. New York, California, and Florida have been the places that have been hardest hit, the quickest—it’s spreading across the country, but obstetricians and those areas are paying between $80,000–$100,000 and up for liability insurance. Now, if you can imagine that you have to get that much to pay your liability insurance before you start paying your rent, your dues to meetings, your personnel, all of your other costs, what that must do to your overhead before you can take anything home.

These are significant problems that we are faced with, and they significantly affect the public. The public has to become aware of it. But unfortunately, as the case in this, and in some many things, by the time that the public is aware and is willing to take action, the damage has been done.

Bachik: Do you think every year it just gets worse and worse and worse—there is no relief in sight for physicians?

Bain: Well, I would not go so far as to saying that. For the first time with the legislature coming up in January, there is a consortium of, well, I heard sixty, and then I heard more than that, of groups that are going to make a concerted effort to get some professional liability limitations across the board. And this is not just physicians, it’s contractors that build buildings, it’s municipal governments, it’s all of the medical profession and its ramifications, it’s architects, it’s engineers, and maybe even lawyers. (Laughs) But anyway, there’s a large group of professions that have now recognized that this is a significant problem and will go back to the legislature and hopefully will get some help in some areas. The whole judicial system needs to be reviewed in that regard.

In a lot of other countries, these things don’t get into the courts at all. In England, most of them are settled by a committee. Patient makes an appeal, and there’s representation from the legal, medical, and two or three other professions, and they decide whether there is damage been done, and if so, what it should be. They don’t get into the courts with it, which is a lot better system. We have more lawyers per population than any country in the world, and they all have to make a living.

Bachik: I know that TEXPAC, for the Texas Medical Association, and AMA also has their AMPAC. When you started into practice, did they lobby as much?

Bain: No, I think this is all part of the changing times. I think these things have developed just like the PACs of all the others. I think it’s developed as the practice of medicine has been more affected by these things and with the advent of the government in medicine.

Medicare went into effect in, I believe it was the early sixties. I’m almost sure it was the early sixties. The effects of Medicare, of course, have been good and have been a significant part of the problem as far as physicians are concerned. When you’re having decisions made at a legislative level that affects practice of medicine, you are going to have an increase in activity by the organizations of physicians that are affected. That one of the crises that we’re facing right now is that Medicare, or let me put it another way.

The payment for health care are the only thing that the government pays for that they don’t pay at the going rate. When they contract for ships or planes or tractors or roads, they pay the cost of whatever that is and the overruns, but in health care they have never paid the going rate. The problems that doctors are facing right now is with the increase in the population that is in the older age group.

You know, for the first time in history, we have more people over sixty-five than under twenty. And the predictions are that the largest increase by age groups between now and the year 2000, percentage increase will be in the over-eighty-five age group. Well, there’s just no way that you can have that high a percentage of the population in the older age group and not have higher costs. So, they froze physicians fees, we’re in the third year of that now, at 1984 level. Well, 1984 level, and that’s all by computer, and that was less than the usual fees then, so those doctors who have a high percentage of Medicare patients in their practice—and our practices tend to grow old along with us, the patients tend to stay with you—so there are a lot of doctors that are retiring earlier than they would because the percentage of their practice is so high in Medicare that they can’t pay their overhead.

Bachik: With all of the changes that have taken place since you’ve entered into the practice, and even though it is probably way far away, do you see us heading towards a more socialized type medicine, like they have in Europe?

Bain: I don’t know. I know that at the present time, the profession is more unhappy than I have ever known it to be because of the uncertainties of the future. A much higher percentage of physicians coming out of training now are going into salary jobs than ever did before. I have this feeling that concerns me that there will be a significant difference in the doctor/patient relationship if somebody else is paying the bill. Doctors are human beings like everybody else, and if the patient sitting across the desk is not responsible for the bill, and the doctor is going to be paid the same amount at the end of the month, whether they satisfy the individual’s needs, I think there is a tendency for that relationship to be affected and that bothers me.

We’re in a revolution of health care delivery systems changes. Corporations are now going in to all sort of organizational things to package medical care. As I indicated a while ago, with the government and employers paying for most of the health care, they want to buy it contractually—they want it packaged. The individual solo practitioner, or small group practitioner, cannot package their wares and sell them, so they’re having to join groups of whatever—HMOs [health maintenance organizations], PPOs [preferred provider organizations], all of those types of things that you’re hearing about. My concern is that it is going to affect the access and quality of care as I have known it during my lifetime of practice.

I think there will be no time that we won’t have all of the facilities and expertise for the big things. We’ll do the transplants and the dialysis and the big technical things, but my concern is for the everyday care for the family of four that has a sick child or that’s having a marital problem and needs some counseling, or that has a child that’s not doing well in school. Those are the things that I see that concern me because I know that in the years that I’ve practiced and when I had families, and I did have three-and-four generations in my practice, that I was able to sit down with those people and answer their needs in a way that somebody who sees this individual and has no background, does not know that family, could not meet their needs.

Our challenge is to try to hold on to what was good from the past, adjust to the changes that are coming in the future, and hope it doesn’t affect both the quality and access to care. But, that’s my concern.

Bachik: Some of the physicians who are entering into their practices now or have been in practice only five years even, I’ve heard them say, “If I had to do it again, I wouldn’t go into medicine.” They would try to go into different fields. Since you have gone into your practice, you’ve now retired from your practice, would you have ever changed?

Bain: I can’t imagine anything that I could have done that would have been so continually challenging and satisfying. I hear that, too, and it makes me sad because I don’t believe that you can take away that satisfaction, and you certainly can’t eliminate the challenges, they will always be there in the practice of medicine. But I know what you’re saying, and when an individual spends three or four years in college, four years in medical school, three to seven years of training outside school, and come out and are chastised or the papers blast for making $70,000–$80,000 a year, and somebody can go into construction and never go into school at all and make that much money, and nobody ever pays any attention to it, it hurts.

Those are the things that we are seeing so much publicity about, and I’m not trying to defend the medical profession, I think there are some areas and some that have gotten out of line. I think there is a real need for adjustment between what we call procedural and cognitive services. The payment for health care has been, and primarily because of the way the insurance companies operate, has been based on procedures. So, somebody who operates can make a lot more money because they operated than somebody who may have saved a marriage or who has taken care of a stroke victim, which was much more devastating both to the patient and to the doctor. There is a move toward adjustment in the cognitive area and seeing whether or not that can be better arranged. We are in for some troublesome times ahead. As I said, we are in a revolution of healthcare delivery. I just hope that we can work through it without having to go until we hit bottom and come back.

Too often in professions, or in, well, I almost hate to say this, but I think the educational system has gone through this sort of a thing and is now going to go back up. When I graduated from medical school, teaching was the greatest profession. They were the people that were most educated in the community, they educated the children, they were respected. The teaching situation has gotten out of hand, and we’re not educating children as well as they used to. Teachers will argue with me about that, but nevertheless, the last ten years it was hard for me to find a secretary that would read and spell and type. So they were not properly trained. Well, I think we’re recognizing the necessity because of the world situation. To be able to compete in the world situation, we’ve got to get our educational standards back up to what they are in some of the other countries. We’ve become a backwards country in education with people who can’t read and write. Well, hopefully we don’t have to go to that degree in medicine.

I was real amused and interested. I went to a great debate on health care costs, not the one that was here in Austin, but one that was several months ago, and it was interesting because the last night of this meeting, they had physicians from Japan, England, Canada, and I believe one other country, that talked about their systems comparatively and the cost. The man from England, he was sort of an extrovert individual, and he walked up the microphone, and he said, “This has been a very interesting two or three days. Here you all are all concerned about what’s happening to you in the socialization of medicine, and I want to report to you at the present time that the private practice of medicine in Britain is now flourishing. We’re building hospitals for the first time since World War II, doctors are now going out into private practice, and it is coming back.” So see, they went too far. The pendulum is swinging back.

I guess it’s the same thing in society and government as it is in families. Children can’t learn from their parents too well, they have to make the same mistakes, and we seem to do the same thing. We should have been able to learn from Britain’s mistakes. We should have been able to learn from other foreign countries where we know what they’ve done. Politics are interesting and sometimes devastating.

Bachik: Do you think we ever will really see socialized medicine in the United States?

Bain: I don’t think we’ll see it in the sense that they have in the other foreign countries for the simple reason—we can’t afford it. We’re already broke, they just don’t admit it in Washington. There isn’t any way [they] could saddle the taxpayers with a health care system when they’re already broke. See, that’s what has financially bankrupt England and is the reason the thing is turning around. They simply could not afford it. And this is what we are running into. The government has promised the public more than they can pay for. As the age goes up, and the demand increases, then they have to do something.

So what do they do? They freeze physician’s fees. Then the physicians are not very eager about taking care of these people that they’re not going to get paid for them. So, as I have already said, I think doctors used to not retire until, oh, mostly in their early seventies. We’re seeing more and more that are retiring in the middle and late sixties, and I think we’ll see more of that because you just can’t operate on 70% overhead. If you’ve got a 70% overhead, since the fees were frozen, in my own practice, now I didn’t retire last year because of that, but it was a one of numerous factors that I considered. Since the freeze went on, my office rent doubled, everything I had to pay for employees went up, the electricity went up, the printing went up, so everything I pay for in order to stay in practice went up, but my fees stayed in the same in Medicare. I raised them a little bit on the other, but that’s not quite fair either. Is it fair to see a seventy-year-old over here who is maybe wealthy, of medium wealthy and charge them a lesser fee than it is a thirty-year-old family who both of them are working, and they have two children and to charge them a higher fee than the one over here because I can’t increase this one. That’s unfair. So, I had a hard time with that.

I feel very strongly that the government ought to be involved in two areas. They ought to be involved in catastrophic illness. With the facilities and technology that we have now, even wealthy people cannot pay for health care in a catastrophe. The government ought to be involved in catastrophe, and they ought to be involved in taking care of those who cannot take care of themselves. The Congress doesn’t like means tests. They don’t like to say above or below a certain amount. But, there is no reason that people who are retired who are getting $30,000 a year or more of retirement pay, plus social security, plus a little investment income, why they can’t meet their needs for their day-to-day health care. So, why wouldn’t it be logical to say for a family below a certain amount or above a certain amount that they take care of themselves until they spend so much in a year on health care and then government kicks in. There are so many things that seem so logical to me (laughs) that are not politically very viable. (Laughs)

Instead of taking care of catastrophe, they have put limits on Medicare and Medicaid for long-term problems. That’s where the people need to biggest help. We’ve got somewhere along the way to pay attention to not just prolonging life but quality of life. That’s an issue that is very difficult to approach.

I just noticed in last night’s paper where there’s a suit filed about a two-pound, nine-ounce twin that the family is suing the doctors at Brackenridge for the care of this baby. Without the technology that we have, the child wouldn’t have lived at all. They saved one of two, but they’re being accused of cutting off the systems that maintain life, but the baby was dead. But when somebody pulled the plugs and the chest quit moving when they quit breathing for it, so now they’re being sued.

Well, there are so many quality of life issues, and so many different, both religious and other things that get into that as to what is reasonable and viable. That gets back to the mobile population and the change in long-term relationships.

When I had been with a family for twenty years in practice, and a difficult situation came up in an older patient, and when I could sit down with that family and say, “We can do this, and this, and she may live another week or ten days,” or “We’re not going to get her back to what she was before she came into the hospital, her quality of life is not going to be good. If this were me or my parent, I would choose to do this and this, and let nature take its course.”

I tried always to avoid making the family make a decision. I made the decision and let them agree with me. I didn’t have any problem with that. When I finished practice in July, I had a tremendous number of so-called “living wills” or statements in my records from patients that said they had talked with me, I thought I knew what they meant, that said, “don’t maintain a quality of life that’s not good for me.” I think the older people can accept that, most of them. You know, death is an integral part of life for all biological species. We’re not all going to live forever.

Bachik: Some of us don’t want to, either.

Bain: That’s right. I think we have somehow gotten away from the face that is a truism. If we do not face up to the quality of life issue and if we simply throw money and technology to prolong life that has no quality and no value, that’s wrong. That’s wrong. I’m not arguing for mercy killing. I’m not talking about that. I’m not talking about doing anything overtly to end life. I’m talking about not doing things that do not have any long-term potential for both lengthening life and the quality of life. I think the public has to help us in this area, and that’s one of the problems in the liability insurance thing. Anybody can sue anybody else, anytime. If you’ve got a large family and you have one individual out of several that is not satisfied with something that was done, that individual can sue that doctor although the majority of the family may have agreed that this was the way they wanted it. But, as long as there is that idea out there that maybe I can sue them and get some money. (Laughs)

Bachik: In closing, what type of advice could you give, or would you give, to the new physician entering who is questioning now, his decision?

Bain: I would say to them that there is no greater challenge, no greater satisfaction. That I would hope that their primary purpose for going into medicine was not primarily money. I certainly cannot argue and do not wish to imply that I do not think people that work sixty–eighty hours a week and make life threatening and life-saving decisions should not be paid reasonably for it. I think that should be a given. That they should certainly not be deterred from their goals but they keep that strong motivation before them, and that hopefully the things that will happen in the future will solve some of the problems that the profession is facing now. In some way, get the doctor out of the middle.

That’s what I’m hearing a lot of. The doctor is in the middle between the patient and the hospital, which is getting paid for a diagnosis and not for what is being done. They’re between the government and the patient in the Medicare. They’re between the administrators of health plans and the patient. Everywhere they go, their prerogatives are being—squeezed as to what they can and can’t do, and should and shouldn’t do.

By and large, physicians have been people who were intelligent and maybe a little too much ego. But it is hard for that caliber of individual to cope with a lot of detail that to them is not helping them in a different situation. That’s where I see the unhappiness. I’m told that my diagnosis has to fit this number for the hospital to get paid, and I’m told that the least amount I do to this patient, the more the hospital will make. Or, if it’s in an HMO/PPO situation, there’s a pool out there that’s going to be divided up that’s left over if we don’t spend it on tests.

We have just so many questions but I do not think those should deter from the appeal of the profession as a whole. And, I hope it won’t because there certainly could not be the same satisfaction from building a building or planning a park that there is from seeing a sick individual get well. That’s the ultimate.

Bachik: I thank you very much for time, Dr. Bain.

(End of interview)