Barton, Bob (Jr.)

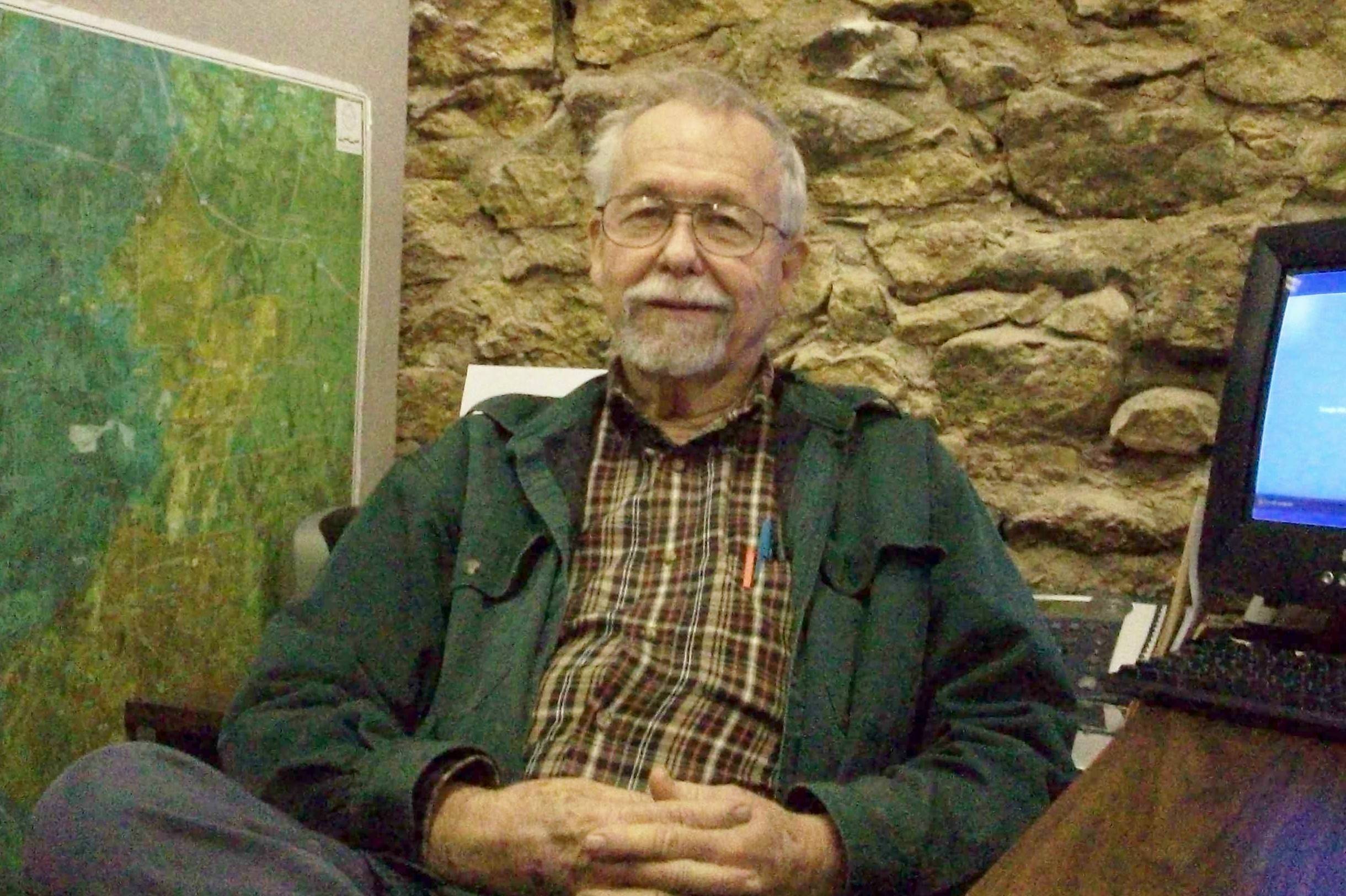

Bob Barton Jr.

Biography

Bob Barton Jr. (1930–2013) grew up in Buda, Texas, and graduated from Southwest Texas State Teachers College in 1954. Along with owning and managing San Marcos' Colloquium Books, Inc., Barton operated a small family ranch near Buda. He published five Central Texas weekly newspapers, including the Hays County Citizen and the Onion Creek Free Press. Barton was very politically active in the Hays Democratic Party and represented District 47 (Hays, Blanco, Llano, and a southern portion of Travis Counties) in the Texas Legislature.

Part of the Texas 150 Oral History Project.

Part of the LBJ 100 Oral History Project.

Two Oral Histories Available

Interview for the Texas 150 Oral History Project

Bob Barton Jr. describes his early life and education in the Buda and Kyle areas, specifically recalling how his cattle-driving family came to settle in Texas, attending Buda High School, and graduating from Southwest Texas State Teachers College after serving in the military during the Korean War. He discusses buying, running, and selling the Kyle News newspaper, as well as operating the Colloquium Bookstore. He speaks about the changes San Marcos and Texas politics have gone through over time, including his work with the Hays County Democratic Party. Barton shares his thoughts about Lyndon B. Johnson and discusses his own run for the Texas Legislature.

Interview for the LBJ 100 Oral History Project

Bob Barton Jr. talks about the common history of the Johnson family and his own family, starting around 1870s, when they all lived in settlements in Hays County. He goes on to tell stories about the Johnson family and Lyndon's rise into politics. Barton also talks about the political landscape of San Marcos and the antiwar movement on campus.

Audio File Access

Full audio is available for this interview. Reading Room access only.

Full audio is available for this interview. Reading Room access only.

Transcript (PDF)

Transcript (PDF) not available.

Transcript

Interview with Bob Barton Jr.

Interviewer: Kent Krchnak

Interrupters: David Sladik, Craig Norris

Transcriber: Kent Krchnak

Date of Interview: November 5, 1985

Location: Barton Properties, Kyle, TX

Begin Tape 1, Side 1

Kent Krchnak: This is Kent Krchnak interviewing Bob Barton in Kyle, Texas, on November 5, 1985, at Barton Properties. Mr. Barton, I understand that you’ve lived in this area most of your life. Could you give me some background on this area and on your family?

Bob Barton Jr.: My family came to Texas on my father’s side— [Interruption]

David Sladik: Hi, Bob.

Barton: I’m tied up right now David.

Sladik: Do you know where Frank’s at?

Barton: He won’t be back until four o’clock. Go out to Mountain City.

Sladik: If you see him tell him I need to get the chainsaw.

Barton: Okay, okay thank you. Excuse me.

Krchnak: Go ahead. I’m sorry.

Barton: My family came to Texas on my father’s side prior to the Texas Revolution, out of Kentucky. They settled near Bastrop, and on one side of the family [father’s side of the family] came on to Travis County near the Hays County line in the 1840s. Then the Barton family itself settled on the place I own, which is west of Buda, between Buda and Kyle, in 1852. So we’ve been in this county about 130 years, basically [a] farming and ranch background into this century. The Depression drove my father into school teaching, and he became a school teacher and school superintendent. So we basically have a rural background in the northern part of the county.

Krchnak: What all kind of farming was your family involved in?

Barton: They went to Newton, Kansas, with the cattle drive in 1872 and bought the place [that we own] with money they earned by taking their own cattle and some neighbors’ too up the trail. So they originally, as most of this area in that period of time in the 1870s and ‘80s, this was cattle country when it was pretty much virgin land. The corn and cotton was limited basically to the river bottoms until the prices went up. By the late 1880s and ‘90s, fencing came in and converted [this area] to [a] cotton economy. My great-grandfather and my grandfather both became cotton farmers and operated cotton gins. [They operated] the Farmer’s Alliance, which was a cooperative gin in Buda, and then when cotton went out in the 1930s, my grandfather and then my father switched from cotton to dairy and [has] gradually evolved over the last ten to fifteen years, basically, back to what it was 120 years ago, [which] was livestock. In my case, it has evolved from livestock into—the price of property has gotten so high that our families sold a portion of their land to subdividers, and so we’re out of—our chief crop is people and progress, if you want to call it that.

Krchnak: What schools did you attend in this area?

Barton: Well, I received my education at Buda High School, which was a small independent school system that was created through the consolidation of a lot of small rural districts. I graduated in 1947 and then journeyed all the way to San Marcos, and with a couple of interruptions for the Korean War, graduated over there with a bachelor’s degree. I believe at that time they called it a Bachelor of Science in Education degree. It was a teacher’s degree with a major in history.

Krchnak: Was Southwest Texas still strictly a teachers college at that time?

Barton: Well, they changed the name. When I was there, I believe it was no longer Lee’s Southwest Texas Normal, but I believe that it did become Southwest Texas State Teachers College and didn’t change to drop the “Teachers” until I graduated. [It] became a university eight, nine, ten years ago. So it was a very small school by today’s standards, [with] approximately two thousand [or] twenty-two hundred students, and of course, when I went there in ’47, it was still in the last stages of being—a lot of older students, a lot of World War II veterans had come back to get an education after spending three or four years in the service. So a large proportion of students were considerably older than I was at seventeen at that time because the war had only been over a couple of years, or barely two years.

Krchnak: So at that time there were a lot of veterans in attendance there at Southwest.

Barton: A lot of veterans. During World War II, it had become virtually a woman’s school, as in World War I. With the end of World War II and in the fall of ’45, a great number of them with the GI Bill in full force [attended Southwest Texas]. I would think probably a fourth of the students or maybe higher were people going to school on [the] GI Bill. Frequently, man and wife [were] both going to school on [the] GI Bill. So, enrollment had gone up some obviously because of that phenomenon that held on for a year or two until [many of them graduated]. A large number of them had a year or two in college before the war. But quite a number were starting from scratch. So there were a number of veterans, even in ’47, that were freshman and had just gotten out of the service—freshman or sophomores—and quite a number of them were juniors and seniors.

Krchnak: What was life at Southwest Texas like at that time? What did y’all do for recreation?

Barton: Well, my perspective is probably not as valid as many because my first year I was a commuter student—

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barotn: —from out east of Buda, where I lived with my parents. Then I went into the service for a year under an experimental universal military training program that was put in for eighteen-year-olds, and when I came out, I came back for a year and did live on campus. Then the Korean War broke out, and I went back into the service and was gone for eighteen months, and by that time I came back I was twenty-one or so and moved on campus for six months. Then [I] bought a weekly newspaper in conjunction with another foolish person. Then I moved off campus and basically went into business and was more of a part-time student. But it was obviously a much smaller, homier environment where people tended to know many of the students. Obviously, the faculty was still fairly small. None of the departments were real large, and if you took something like geography there weren’t—or economics—there weren’t but one or two teachers in that particular field. So, it was a pretty good school, and I don’t feel particularly deprived from having gone there rather than to one of the larger or more prestigious universities.

Krchnak: This newspaper that you had bought when you were at school at Southwest. Was this the Kyle News?

Barton: Yes, it was the Kyle News. I had some passing interest in journalism. I had one journalism course so that, at twenty-two, I guess you think you’re an expert (laughter). [It’s] very easy to believe you are an expert. I bought the little newspaper here in Kyle that was getting ready to be consolidated with the larger paper in San Marcos. The old man that owned it had… his equipment was obsolete. He had reached the end of his rope, economically. Both my partner and I were living on the GI Bill and making $150 a month. We felt like we could go into—with that large amount of sums—we could go into business. So we bought the newspaper, really knowing almost nothing about business certainly and not too much more about newspapers. It was a very, very interesting experience, one [that] I enjoyed, but not the swiftest financial move I ever made in my life perhaps. Except it was cheap. It was in my price range.

Krchnak: Was it a weekly newspaper?

Barton: It was a weekly newspaper. It had been one of the last hand-set weekly newspapers in the state. We had the good fortune that neither one of us knew how to set type. But there was an old gentleman, an old Mexican-American gentleman, who I think was probably a Mexican national, who was the printer here on the paper. We bought the paper on a Friday and on Sunday he died (laughter). So, one of the benefits of going to college—we were frightened, and it was at the beginning of spring break, and we went down to register full of fear and trepidation. On the next day, [we] were reciting our woes to somebody in the journalism department where we were signing up for, belatedly, for some additional journalism courses. The man standing behind us, an older veteran, had just gone bankrupt in Mississippi in the newspaper business. So, we sort of hired him on the spot to come in. Without him, we probably would have never gotten our first issue out because we just didn’t have any of those basic skills as far as actually setting type. We thought we could write a story and maybe sell an ad, but [we] didn’t know anything about the physical work or didn’t have any of those physical skills. We learned a lot over the next few months, and both of us continued to go to college, and this other student came down, and we basically ran the newspaper when we weren’t in class. We were both natives of Buda, which at that time [there was] quite a rivalry between Buda and Kyle. We went in with one strike against us coming out of Buda buying that small business. He still lives here. He later became coach here after I bought his interest. We traded interests for a number of years when one of us would get broke. But he ended up being a coach here and then superintendent of the schools of this large, or what became a large consolidated school. So it, the little business venture, did end up centering. I married a Kyle girl later on. So we both have centered. I have lived in San Marcos and the general area most ever since.

Krchnak: How large were Buda and Kyle at that time?

Barton: Well, not as large as they are today. I mean both of them. Kyle was a little larger. Buda was a little hamlet of three hundred people, and it is not much larger. The business district is no larger. Obviously, now with Austin’s growth, it is growing faster than Wimberley is. [They were] very small county towns, and really up through World War II and really until the interstate came through, even though we were this close to Austin, [they were] pretty provincial, off the beaten track communities. It had a downside but certainly had an upside to it too. The pace of life was a good bit slower. We were waking up to the fact that there was a great big world out there because television came in within a year or two after that in the early fifties. People tended to become, perhaps certainly not cosmopolitan, but at least expanded everybody’s horizons considerably.

Krchnak: How long did you have the newspaper in Kyle?

Barton: Well, it’s really got a pretty complicated life. Bill “Mo” Johnson [the partner] and I bought it, and we ran it for about a year. Then I graduated before he did, and I went off and took a teaching job because it really wouldn’t support one family, but it certainly wouldn’t support two. He was married, and I was not. So, I took a teaching job and then later married that year, and he ran it a year. He then graduated and was offered a coaching job here [Kyle], so I bought it back from him. [From] my recollections, we basically bought and sold things through the barter system or based [it on] the assumption of debts. At least in one—he says once I bought it from him for assuming his debts and gave him a box of cigars. One time he bought it from me, which was the earlier time. I believe he paid my phone bills to my girlfriend, and later wife, and took over. But I ran it for a number of years, sold it, and went off after I married and worked on some daily newspapers out of state. [Then] I came back and bought it two different times and eventually moved it to San Marcos, and [I] ran a much larger newspaper there—

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: —until about seven years ago, when I sold out to a chain that consolidated my paper and the Record into one. So it led a checkered career, and actually I guess we’re through the back door coming back in. By that time my son had finished college, and I had bought a little paper in south Austin and moved it to Buda and then sold it to my son. So he’s back in putting out a newspaper in this general area.

Krchnak: Is that the Onion Creek Press?

Barton: Onion Creek Free Press. Yes. So I guess there is some, not direct continuity, but at least by stretching a point you can say at least my family is still engaged in the newspaper business.

Krchnak: So you were involved in the newspaper business for several years.

Barton: On and off for about twenty years. I’d starve out a time or two, and I actually started the Colloquium Bookstore basically to keep my head above water in San Marcos. [I] at least was smart enough to realize that when it started taking off much faster than the newspaper that I ought to hold on to it, and it sort of provided food to put on the table while we continued to work at trying to turn the newspaper into a success, and we eventually did. But it took a lot of years, a lot of energy, a lot of time, and a degree of luck or stubbornness, I suppose. So I’ve spent about twenty years in newspapers in the county all together.

Krchnak: Could you give me some background on the Colloquium Bookstore you have in San Marcos?

Barton: Yes, it was basically started twenty years ago this year in the backroom of the newspaper that was located at that time in a building adjacent to the State Bank. It has since been torn down. So we put it in the front room, and we put the newspaper in the back to basically help pay the rent of $200 a month or whatever we were paying. There was only the state-owned campus store, which at that time is typical of a lot of monopolistic businesses. [They] had rather autocratic rules. During registration, people would be lined up buying books and [at] four o’clock they would shut the doors whether it was raining or whether people were finished with what they were doing or whatever. We had started just a regular trade bookstore because we didn’t have a lot of capital. My wife and I had a number of other people that [were] involved in the newspaper decided that something as poorly run as the university store probably needed some competition, and basically again without a great deal of knowledge about what it would take as far dollars and merchandise or anything else, we decided to get into the textbook business.

So we took our credit in our hands and basically bluffed our way into buying a building closer to campus and started ordering books. The university was growing, and there was a good bit of student dissatisfaction with the way the other store was being run at the time. We were lucky enough in our first year to sell every bit of merchandise we had, which gave us enough capital then to buy some more. Someone else had the same idea and opened up down the street from us and either partly through luck, but largely through hard work and energy and willingness to work long hours, we survived and the other store didn’t. It proved as the university continued to grow that, and they improved their policies of course at the university store fairly quickly, that it was a big enough place for both of us to make a living. We’ve moved several times since then into larger accommodations. [The] first two or three years, we [would] do as much business in one day during registration as we’ve done the previous year, and of course we ran through that pretty quick. But it has continued to grow, and we were also blessed in those early years by perhaps being in the right place at the right time. [We were] identified in the late sixties and early seventies as sort of politically more sympathetic with some of the student turmoil that was going on, in the sense that both in the anti-war movements, [and] also there was a big fracas in San Marcos involving everything from dress codes to lifestyles to a lot of other things, and because we were progressive or liberal in our politics or in issues particularly involving people, that it was probably beneficial. [It was] just that general feeling we had about people at that period of time that turned out to be very good for our business.

Krchnak: It helped to draw people into the store.

Barton: It helped to draw people. We were rebellious although we were sort of an old family and had deep roots in the community. San Marcos had a lot of political turmoil and political strife in those years. Myself and a number of other people that were associated with me were deeply involved in the political developments that occurred in the county involving city politics, school politics, and state politics. There was a period [also] with the student right to vote issues. Coalitions formed basically between progressive Anglos, the very large Mexican-American population, and students into one of the bigger, larger political forces within the community. [A] by-product of that, although I had a lot of enemies, and I still have a few in San Marcos because of that involvement from the way I made my living, [was] attempts to ostracize me or punish me by some people within the business community. [This] really drove students even more into defenses with me.

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: Now it came back to haunt me fifteen years later when basically the student vote—different students in different times and different attitudes as a candidate on the Democratic ticket. I got swept out of office by the younger brothers and sisters of—

Craig Norris: Excuse me, Bob.

Barton: Yeah.

Norris: Do you need to tell me anything, or do I need to know anything?

Barton: No, other than David Sladik’s looking for you.

Norris: Okay.

Barton: He wanted to borrow the chainsaw, and I told him he had to clear with you. So, I wouldn’t worry about it.

Norris: Okay.

Barton: But I’ll be around tomorrow or later this afternoon. I’d like to go down to Buda maybe sometime tomorrow—

Norris: Okay.

Barton: —and get you to look one more time at that property with me.

Norris: I’m going back into San Marcos.

Barton: Okay.

Norris: I just met with the state out there and—

Barton: Oh, did they go with you?

Norris: Yeah.

Barton: Great.

Norris: I met them out there.

Barton: Good, did he say—what—going to take a—well, I’ll talk to you when you get back. I need to finish an interview. Alright. Sorry.

Krchnak: I’d like to ask you, too, about [politics] since you have been involved in politics in this area for a long time. I understand that you were co-chairman in 1968 of the Humphrey-Muske—

Barton: That’s true.

Krchnak: In Hays County.

Barton: That’s true. I’d forgotten about that. I really had been a Gene McCarthy supporter, but when he lost out I—because nobody else was around, and I am basically a pretty staunch Democrat, or anti-Republican at least, put together the campaign in ’68. [I] have been deeply involved or at least somewhat involved in the Johnson campaign of ’64 and Kennedy campaign of ’60. In ’68, whatever campaign we had, Humphrey carried the county, even though [he] lost the national race. I also ran the disastrous campaign of ’72, the McGovern campaign, although I had not been a staunch McGovern supporter prior to the convention. Where we really got wiped out, we found out early that although in ’69, the late sixties and early seventies, [that] the students were basically—there was a lot of belief that ’72 was going to be the year of youth and the year that the youth of American taught their elders a lesson. Well, the lesson they taught at least at Southwest Texas and other places were that they went down and voted for Nixon in droves, just as most of their parents did.

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: The students weren’t much different. [That was] something I already knew, but it helped reinforce it. Many townspeople were frightened to death of the students getting the right to vote, and [they thought] the students would take control of the city council. [They felt] students were radical [and would] have marijuana shops on every street corner. The same sort of fears that they had about blacks and Mexican-Americans they had about student because they thought all students were monolithic, and all students were liberals, and all students were dopers, and all students had long hair, and they found out by the time the student did have the right to vote that most students, in general, voted [about] like their parents did.

It was a fairly conservative student body in that the Hays County, and particularly the student boxes since ’72 have been, particularly the younger students from the dorms, vote very, very conservative, very Republican. But before they got the right to vote, the students basically did get treated as second-class students. They didn’t hesitate—I mean the police treated them differently than they did before they became voters. There was some harassment by some police and some people in power, you know, [these] people looked a little different and dressed a little bit differently. So, the right to vote, although it usually isn’t exercise anymore by students except in national presidential years, it probably helped changed some attitudes here. Obviously, it helped bring about for a number of years where we operated in coalition with students. It brought about some progressive mayors and changed the interworkings of local government, both the city and the school, the school board at least.

Krchnak: When you served as co-chairman in 1968, you were on there with Bill Pool?

Barton: Yeah.

Krchnak: Is that right?

Barton: Yeah, Bill’s always been very active and [a] staunch Democrat. Bill goes back even further than that, but he was basically—usually a number of college profs that were involved, some as I say, that was prior to the students that were under twenty-one being allowed to vote, although we had a fair number of students—the Mexican-Americans had already emerged as sort of a driving force—[there] had already been a Mexican-American elected to the city council in San Marcos, but not to any county office. There were a number of Mexican-Americans that—we don’t have a very big black population, of course, in this county, but there was sort of a mix of a rural populist, brass-collared Democrats. So, it was sort of an interesting mix of people, but Bill sure was involved. Yeah.

Krchnak: You also served as the Hays County Democratic Chairman in the—

Barton: Yeah.

Krchnak: Seventies?

Barton: Yeah, I guess maybe in ’70, probably seventy—

Krchnak: Elected in ’74.

Barton: Yeah, good, okay. I had been very active. The Democratic Party in this county and in this state had been pretty monolithic. If you weren’t white and middle-aged, you didn’t have any power, and although I was white, I wasn’t middle-aged at that time, and a number of us in the sixties were determined to, particularly when Lyndon Johnson was President, we had been embarrassed by the fact that all the Johnsons—both on his war on poverty and the civil rights issue—that within the county, within the structure of the [Hays] County Democratic party, that people were not very supportive of him. Within the leadership or [within] the county leadership of the Democratic Party, even though Mexican-Americans supplied 35–50% of the vote generally, there was not a single Mexican-American precinct chairman.

So, we started on a concentrated drive in the late sixties to persuade or force the leadership of the county Democratic Party, or the hierarchy within the party, particularly within the county courthouse, to pay attention and at least give those of us that considered ourselves national Democrats, or basically party loyalists, a sort of a piece of the pie, and it was resisted greatly. I had run in—a number of people, a couple of college profs, and four or five people would run for—for about six years there, we would run for [Hays] County Democratic Chairman and lose by about 60%–40% majority. Then with the students’ right to vote and with the growth of the Republican Party that started evolving in the seventies, which drew some of the people out of the Democratic Party into the Republic Party— I guess in ’68 or ’69, the chairman of the party died, and we were able to put in Dudley Dobie, who was a progressive, old-line, but a loyalist Democrat against a more conservative Democrat, and he served four years and decided not to run. We basically connived to disguise the fact that he wasn’t going to run until the last day of filing because I had been very active within the—what we called the Hays County Independent Party. We were really a third party. We participated in the Democratic Party politics, but our goal was to reform and change the Democratic Party. So we called ourselves “independents” and tried to use the creative energies of that group to bring about reform basically from within.

Anyway, I was highly controversial because of a variety of activities. I actually filed five minutes before the filing deadline, and he did not file. So I was the only name on the ballot, much to the dismay of the old guard Democrats particularly in San Marcos. They mounted a write-in campaign, which is generally not successful in anything, and spent a great deal of money and a great deal of energy, too. They picked a very popular and very nice banker’s wife with some prestige and who was a good Democrat to run against me. So we had a heated campaign, and I guess I call it a mark of sting, although I won, I think I had nearly two thousand people who disliked me enough to write in somebody else’s name. But by the time the next election came along, many people found out that I didn’t have horns, and I was, I’m basically, I certainly consider myself a progressive. Many people [thought] that I was too liberal for this county, too progressive, whatever word you want to use. But I’m basically a compromiser, and I think I’m pretty much of a midstream Democrat, and by the next time the election came around, I think the write-ins decreased about to only three or four hundred diehards. So I did serve about six [years], three terms I believe.

Krchnak: So that kind of got you interested in politics?

Barton: Yeah, I’d always been interested, deeply interested, in politics. I’d been involved in a lot of other people’s campaigns, generally on the losing side. I hadn’t, until Mark White got elected governor, I had never voted for somebody—well, I guess that doesn’t even hold true there. I voted for somebody else in the primary [instead] for him the first time. I voted for Bob Armstrong. But my favorite usually didn’t get, you know, didn’t make it all the way. So I’ve been interested in politics in that sense, although I came out of—my father was much more of a conservative, is a conservative Democrat.

So, I’m not sure what turned me into much more of a progressive, but a number, obviously a lot of factors [were] involved. I’d always basically been a party loyalist, or a strong believer in the two-party system, and at least picked the one out that was closer to my view. Although frequently, sometimes, I’ve held my nose and supported the Democratic candidate. So, I was active as one of a number of people integrating the Hays County Democratic Party, and it happened throughout the state of all sorts of people. I mean of women, of blacks, of browns, and young people, and all sorts of people, and it is no longer monolithic. There’s no longer just the group of middle-aged people involved in any sort of leadership role. I take some pride in that happening, and [I] certainly don’t claim anywhere near all the credit because it was a collective effort by an awful lot of people.

Krchnak: Did you personally know Lyndon Johnson? Ever meet him?

Barton: No, I was not, I mean, I met him because he was my congressman. He sent me a letter when I graduated from high school, as he did to everybody. I, like a lot of people, had basically been a Johnson supporter. My family had been when he was in Congress and then when he ran for the US Senate before my time, before my adulthood, and my family had supported him. I basically belong to a little bit more liberal wing. I was basically more of a Ralph Yarborough Democrat in Texas.

So in the fifties, I was sometimes disappointed with him and not always on his side in Texas, at least at the [Democratic] convention of ’56. He could be a very aggressive, very persuasive, but also a very aggressive person, and he had some personality traits I didn’t admire. He was a flawed person, like we all are. But I generally always ended up supporting him when it came down, certainly when it came down to a choice between a Republican and a Democrat. I never had no intimate association with him other than being in the same room with him and a couple of times at state conventions where, I wanted to say conventions, in the mid-fifties, where it was very close over the choice of a national committee man, and he high-pressured Hays County people. I was young enough at the time that it didn’t work with me. (Laughter) Although, I saw it work with a number of people who had more to lose than I did, I have some admiration for his skills along those lines.

Then when he became President because he was embracing—did—and he genuinely—I was a much greater admirer of his grandfather. His grandfather was one of my heroes. He, his grandfather, was a populist state representative from this district. His grandfather grew up in Buda and lived in Buda before they moved to Johnson City. So among the two, I chose his grandfather and his father, and then him. I want to make it clear that I didn’t dislike him. During his presidency I was a great—I considered myself a strong supporter of him. When he ran for re-election, I was certainly a strong supporter of him. There was some resentment by some of us, not towards Johnson, but because some of the key Johnson people in San Marcos at the time supported none of his policies but were in a position of power. Whereas people who supported his policies were sort of on the outside, and that’s frequently true of a—know—within your own community, no great leader is—everybody knows all of his blemishes, and [they] sometimes don’t weigh all of his attributes. “The prophet is born without honor in his hometown”—that sort of thing.

There were a lot of Lyndon Johnson haters in San Marcos. San Marcos was full, not full, but there was a large [group of] minority people that really hated him passionately from back, if you read Caro’s book, when he was a student politician. Because he had a tremendous willpower and a very engaging personality, he could get people to work long hours for him and take some personal abuse. [He was] a very brilliant, talented person. So with all these asterisks by it, I guess those are my feelings about him. I’m proud of the fact that he comes out, that he was—I like Caro’s early chapters, in particular, because I really think he was a product of the environment or the land that he grew up in, [in] which he had a personal experience with—there were a lot of people poorer than the Johnsons, but the Johnsons were bright and talented people. As far as economics, they suffered during the Depression like anybody else did. I think he had a great empathy for people that fell into that category, and I feel like I do too. It would have been nice to have known him under different terms, or being at an age perhaps where being a little bit older, being a little bit closer to him, but I’ve known—the woods are full, everybody’s got Lyndon Johnson stories or Sam Sr. or Sam Jr., his father and grandfather. They were all intertwined with this district. They had relatives and friends and close associates, but I wasn’t one of them.

Krchnak: What made you decide to run for the Texas Legislature in 1982?

Barton: It was basically a number of factors. One, of course, [was that] the incumbent, Don Rains, decided not to run, and that threw it into a wide open race. A new district was created that sort of centered up and down the interstate. I lived in the middle of it. That was another factor. I had reached a place where early in my youth, in my early twenties, I had seriously thought of running. [However,] I was hungry and poor and didn’t have any money. It didn’t take a lot to run in those days, [but I] couldn’t have won. Also, by the addition of south Austin, that politically I was probably in the mainstream of at least the Democratic Party within the district. [I] had the time and could afford to run, and [I] had a lot of people encourage me. I guess one of the things I thought—why not.

As it turned out, we had a very bitter Democratic primary between myself, or it ended up, there were three of us. It ended up with someone who had been an ex-employee and a close, at one time, a close friend. It turned out as frequently happens among people that have been—into being a somewhat divisive and bitter campaign. Which in retrospect, it would have been nice if it hadn’t happened, and some of those wounds, most of those wounds, have healed to some degree. But they never completely heal, of course.

Krchnak: Was the primary forced into a runoff election?

Barton: I missed winning without a runoff by forty-seven or thirty-seven votes. I don’t recall how, and there was—it was a three-way race, and the third candidate just got enough votes to leave me a little bit shy. So we had a pretty brutal runoff that resulted in me winning by a comfortable margin because basically the decision, not so much by my opponent, but by his advisors and his hired hands to run a mean campaign. As frequently happens, it reacted adversely to them and cost them votes rather than helped them because, at least in the Democratic Primary, at least in this county, people had already made up their minds about me one way or the other before that campaign even developed. Some people liked me and some people didn’t, and this probably [had an] influence to some degree.

Bill Cunningham, who was my opponent, had been one of the student leaders back in those student movements. [He] had never been, certainly not a student radical, but because he had worn his hair long and because he had been associated with other students that considered themselves, by San Marcos standards, to be radicals, he had been branded as such. He had been elected to the city council by this coalition, so they considered him to be much more liberal than he was when he was a student leader and immediately thereafter. His attempts to move real far to the right just didn’t wash real well. It appeared he was moving farther than he was. He really didn’t have that far to go I don’t think. So I understand where he was coming from, but the public perception was that, well one, he was young and that he was not—he was working for Pedernales Electric, so he was basically a hired hand of the electric cooperative. That appeared on the surface, and I feel that he probably wasn’t as independent as I was. There was a difference of twenty-five years in age or thereabouts.

So there were some factors out there working that I had thought at the beginning of the race that would work in my favor and it turned out they did.

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: Then I had a relatively easy campaign against a very bright, young Republican lawyer. But two years later, of course, it was a different matter. Tides come in politics, and tides go out. The unpopularity of the Democratic nominee, and also the great growth in the district, where although all polls that I ran showed me way ahead—

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: —in name identification, and I didn’t have many negatives that Austin was full of people and Hays County was full of people who didn’t know who I was, didn’t know who my opponent was. When you have to make a choice like that, you usually go back to the choice you made at the top, and Reagan ran wild in this district. Doggett, who had represented the Texas Senate, and had been a good senator—

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: —ran poorly too, to people’s surprise. I ran about fifteen points ahead of the President, [I mean] of Mondale, but that wasn’t far enough ahead, so I went down. The person who ran against me, Anne Cooper, was a popular person, well-known in San Marcos, and people liked her. She hadn’t made anybody mad. I thought at the time, originally thought that as long as the Democratic presidential candidate was fairly close, that I could win. In the last ten days, no one else believed it, but I wrote down my predictions that I was going to lose, and I did. But—

Krchnak: The election was close, wasn’t it?

Barton: Close. I got 49.3% of the vote. It was very close. But, I basically lost it in the student boxes where the Republican campaign was well-organized. Ironically, the same people in town that accused my associates, and particularly in the Mexican-American community, of loading people into cattle trucks, basically, and marching them down to vote in unison for Democratic candidates. If anything occurred in 1984 in San Marcos, it was a well-organized campaign within the campus student community to marshal that kind of influence—well-organized bus trips down to vote. There is nothing illegal—

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: —or even particularly unfair about it. It happened basically in the student boxes where, the two big student boxes, Republicans racked up the majority that I lost. Looking at it in retrospect, it was a rather interesting and humorous reflection on some of my earlier involvements.

Krchnak: Are you thinking about running again this next year [1986]?

Barton: Yes, I am. I’m probably 90% or maybe more sure of running. I’ve enjoyed not being in office. I’m pretty much of a political animal, but I’m not, at least at fifty-five, I’m very interested in being my own man, my own person. Being one of the 150 legislators, I’d enjoyed it, and there’s some—everybody’s flattered being an elected official, and certainly there’s a good side to it, and there is a—I certainly feel like I was a pretty good representative. I don’t have any delusions what one person out of 150 can do, as far as some of the kind of legislation I’m interested in. I’m not very much of a team man in anything, and so the Speaker of the [Texas] House who is going—you running out?

Krchnak: No, it still has a little.

Barton: The Speaker of the House who is going to be re-elected this time, and probably the rest of his life if he wants to, is not one of my close confidants. I really don’t consider myself an enemy of his. He treated me fairly my freshman term.

Krchnak: Gibb Lewis?

Barton: Gibb Lewis.

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: But we have a lot of basic disagreements. I’m not a strong believer in some needed reforms as far as tax policies and a number of other things. Being one of a 150 and not being on his team means that I’m not going to accomplish a whole lot in the 120 days the legislature meets. On the other hand, I have some skills as a politician, as a negotiator, as a compromiser, and the other roles a legislator plays in everything from Edwards Aquifer to little disagreements within the various bureaucracies in the state that sometimes at least can be straightened out or changed to a slight degree. I have some skills along that line.

As far as representing this district in the various manifestations of political intrigue, I think I’m pretty good at it. The county would be better off with me than with Mrs. Cooper, who is a very nice person, and who doesn’t vote—even though she’s Republican—probably didn’t vote that much differently than I would have voted. I don’t think she has those kinds of skills. She’s more of an observer than a participant.

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: I think she needs to be replaced by somebody stronger. I’ve kind of looked around hoping someone would emerge that had the money, could raise the money, that had the time to serve, and that would be independent from the obvious many forms of lobbying that I disagree—the lobbyists that I disagree with are not only being lobbyists but [are] with the powerful interests in the state that I disagree with. Nobody has shown up yet, and the time is kind of running short. I’ve sort of reconciled myself to running, not that I wouldn’t enjoy serving. I even enjoy part of the campaigning, but it’s a long and arduous thing.

You have to stop doing some things that—

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: I’ve spent a good bit of time in Colorado. I’ve got a place at ten thousand square, ten thousand feet in the sky, and I’ve enjoyed myself. I’m not much for the banquet circuit, and I’m not totally infatuated with ribbon cuttings and all of the other things that—some of the glitter that goes with political life. I’m also a partisan Democrat, and I want to win it back. I think a Democrat—there is a possibility of a sort of a progressive coalition eventually establishing itself in the state and the state legislature. I’m willing to be at least a cog in that. So, all those things considered, in all probability I’ll run. But there might be a knight on a white horse show up in the next two or three weeks, and I’d defer to him or her. If they don’t, I probably will run.

Krchnak: As a final question, I’d like to ask you how do you think Hays County and this area has changed, what has changed the most say, in the last thirty to forty years?

Barton: Like a lot of people my age and a lot of people that sort of consider themselves rebels, or rebellious from the life that we grew up in, you’ve got a love-hate relationship with Texas as it once was. We were racists, and we were very provincial. [They] were sometimes cruel in small towns to people that were certainly—I mean, there was a great deal of pressure for everyone to live the same sorts of lives and live by pre-established norms. Like a lot of people, I rebelled against that in youth, and [I] am still rebellious against that sort of thing. I prefer a more multi-cultured, multi-faceted kind of life that includes all kinds of people. As the county has grown, as the communities have grown, the pressures for everybody to think alike and be alike and to be totally provincial in their outlooks and think that Hays County is the center of the universe, and we’re the most important people, and we’re blessed by God to rule whatever world we live in, [has changed]. That you shouldn’t listen to divergent opinions and uppity women and blacks and browns and young people and all sorts of folks shouldn’t have equal access to all the better things in life [has also changed]. I’ve seen many of those changes occur, and there is a much better life for most people than certainly there was in the end of the Depression when I was born or in those early years in the fifties, where we sort of had to—if you didn’t march in step with everybody else, you were at least suspect. I’m glad that’s changed.

But there’s a downside to that, too, to becoming a more urbanized society. You did have more time to smell the flowers, and you did have more time to get to know people. There was a more relaxed atmosphere. The summers that you could go, and that people went two weeks to the river and camped out or whatever. There was a bigger, stronger family tie.

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: There’s some things about urbanization, the six hours in front of the TV that too many people spend every day; the reluctance to, as we become more urban to get involved in other people’s lives; to rub shoulders against other people and be affected by other people; to withdraw from participation in the total community, bother me greatly. I have some nostalgia, like most people do for people my age, for prior times—

Krchnak: Uh huh.

Barton: —for those days. I don’t think I’m one that would like to be nineteen again, and I don’t even want to go back to 1950, because 1950 in Kyle was pretty, or 1955 in Kyle, you had to be pretty tough to dare to be different. You don’t have to be that tough anymore to dare to be different. It also bothers me that too many people still are willing to let somebody decide for them the kind of life they are going to live and not to question authority. It’s easier to do that now. Unfortunately, sometimes people get too occupied with other materialistic things in life, and I think we’ve conditioned our children to some degree to think that life is going to be better. Unfortunately, it may be worse—

Krchnak: Uh-huh.

Barton: —for the people, you know, the ecological problems we have, and certainly the threat of the bomb and other things. Anyway, that’s a loose-jointed wrap up for you.

Krchnak: Well, thanks a lot, Mr. Barton.

Barton: Well, I enjoyed visiting with you about it, and I’m glad you’re into this project. I hope you get out and get a lot of interviews. It’ll be interesting to someday go back, and [you] might not particularly listen to mine but listen to other people. I already know what I think, at least as of this day.

Krchnak: Well, thanks a lot.

Barton: Okay.

Krchnak: This concludes the interview with Bob Barton in Kyle, Texas on November 5, 1985.

End of interview

Interview with Bob Barton

Interviewer: Barbara Thibodeaux

Date of Interview: March 6, 2008

Location: Office of the Hays Free Press, Kyle, Texas

THIBODEAUX: Bob Barton, a Hays County native, longtime newspaper publisher, former state representative, former Hays County Democratic Party Chair, and a 1954 Texas State University history graduate. Mr. Barton is currently the publisher of the Hays Free Press serving Hays County and southern Travis County.

THIBODEAUX: This recording is part of the LBJ Centennial Celebration Oral History Project sponsored by Texas State University. Today is March 6, 2008. My name is Barbara Thibodeaux. I am interviewing Bob Barton at the Free Press in Kyle, Texas.

Mr. Barton, even though you have agreed to the terms and conditions of the release pertaining to this interview in writing, will you also verbally acknowledge your acceptance with a yes or a no?

BARTON: Yes.

THIBODEAUX: Thank you very much.

I thought we’d talk today—I don’t even know where to start with you. (laughs)

BARTON: Okay.

THIBODEAUX: Just maybe some background information because I know your family goes so far back, and I’m not sure if they may have known the Johnson family early on.

BARTON: Well, of course, Lyndon’s grandfather lived in Mountain City, which was the original settlement here before there was a Buda or a Kyle, or lived near the edge of Buda actually, of what’s now Buda but was not then. So, yes, our families go back into the 1870s, not necessarily intimately but as a member of the same community, which was generally called Mountain City. And it was no town, it was just a settlement strung along the stagecoach line between Manchaca Springs and San Marcos. So they did go a way back, and because I’m an amateur historian, I’ve certainly done some reading of the early newspapers and gathering of some recollections and perhaps some mythology involving the Johnson family in the period, of course, before Lyndon was born and about the time his father was born was when they lived there. So, yes, I do have some information that goes far back.

I was not an intimate friend or even a friend of Johnson. I was someone who probably voted for him every time he ran when I was an adult. And my grandfather and his father had a friendship, to answer you generally.

THIBODEAUX: Can you describe that relationship?

BARTON: Well, let me go back—and I don’t know what sort of order you want. There’re some great—Johnson—I think his grandfather after the Civil War moved to what is now the city limits of Buda on Onion Creek and had a farm there at what was then called the Mountain City Onion Creek area and participated in community affairs and was active in. One of his daughters, who would’ve been Lyndon’s aunt, was “queen of the may” there sometime in the ‘70s, very active in the community.

And old-timers tell the tale of Lyndon’s grandfather intervening in a argument where one of the local “bad men” [Speaker is saying, “With quotation.”] I don’t know how bad he was—but at least an aggressor—interrupted a fight between two men. The loser in it being a unnamed farmer or neighbor of his, and in the exchange of the dialogue between Johnson and the winner of the fight, this man threatened Johnson’s—to either whip him or shoot him. I’ve heard it both ways. And that that was one of the reasons—and perhaps not the major reason—that he moved on to Blanco County and the Johnson City area, where he already had relatives. I’m sure it’s more complicated than that. He had a large—quite a number of children, five or six—I don’t know how many. You know or somebody does—and that that was one of the reasons that he decided to leave. Those were—I’m sure, opportunities to do better would’ve been a factor.

I had an old great-uncle that lived—Edwin Nivens—who lived to be ninety and told a story. Of course, Lyndon was congressman and then senator and then president, so this must have been about the time—he lived to be almost a hundred. So it would’ve been sometime during Lyndon’s presidency that his story on—his recollection about the Johnson family was that when they moved and left Buda, that Edwin Nivens, having been the first baby born after the town was founded in 1881, that he was a small child. And when they left the neighborhood that they either stopped or visited with the Johnson family and the Nivens family and that Lyndon’s father had taken a fancy to a marble, what he called a steely, which was a steel marble that you played—and was somewhat younger than he was and cried to have it. His father made him give it to Lyndon’s father, and so in a jocular mood said, “I don’t know if I’ll vote for Lyndon or not because his daddy took my favorite marble when I was a little boy and never did…I cried about it.” So there were those sort of relationships.

Lyndon’s father moved to Johnson City or to the Johnson City area and then in the ‘90s—and you’d have to check the—his father ran for the legislature as a populist back during the part of the 1890s when the populists and the democrats were struggling and farm prices were bad and business was bad. So he did some campaigning here and all over. And some of the early day Hays County newspapers have a little bit of information there, and he ran and lost but carried the Buda section—or what by that time it was Buda—because at least most of the people there remembered him with fondness. When he left the county, it was at least because he’d done a good deed, according to that particular story. Then much later when Lyndon’s father was in the legislature—so there was that connection.

So that when his father got elected to the legislature after the turn of the century, that I think he came by buggy to Buda or caught the train in Buda and would ride to the legislature for the session at least. So they retained friendships there that lasted into Lyndon’s time. There were still families and Lyndon was good at mining that sort of relationship that gave you some feeling of belonging. So at least the Buda area in those have a claim to some familial relationship with them.

THIBODEAUX: So did your father have any type of relationship with Lyndon?

BARTON: Of course, Lyndon when he was running the National Youth [Administration, NYA] —when he came back to Texas from having worked with Congressman [Richard] Kleberg, that he took the NYA job, he was living in Austin. And so he renewed acquaintanceships and through running NYA, plus he’d gone to, of course, school at Texas State. My grandfather, Henry Barton, had married a—courted in the 18—late ‘90s a woman from Willow City, which is in Gillespie County, but it’s in the vicinity of Johnson City. Anyway, and so his story was that he and Lyndon’s father had courted together during that time, so those were connections that everybody have. Some of them perhaps exaggerated, you know, as Lyndon rose somewhat to fame. But that was not an intimate relationship.

Lyndon, of course, ran for that first election. In fact, when I was down for the Obama rally, my earliest recollection of his going there in the summer, I believe, of ’37 when Lyndon announced for Congress when Buchanan died and along with six or seven other people in the Tenth Congressional District. And he ran—I have vague recollections of going with my father. My father was superintendent of the schools at Buda at the time. My grandfather was—nearly everybody were New Dealers in those first years into the ‘30s at least. So he’d been a farmer and ran a cotton gin and because—I’m sure familiar relationships and there were only a handful of republicans in any of the small towns, one or two families, so that when the presidential—the times that republicans won the presidential election, somebody was going to get to be postmaster, which was a good job. So every town had one or two republicans and one or two drunks, you know. Maybe more than one or two drunks. So, yes, there was that sort of friendly relations and obviously some neighborhood recollections that created friendships within one of Lyndon’s—and you probably need to—he’s dead. Sherman Birdwell is dead, but he worked for Lyndon as a NYA guy, then continued to—he ran one of the funeral homes in Austin. Anyway, there were a lot of connections through the years that Lyndon—because he had some Kyle connections too with the Bunton family, which were related on his father’s side too. His father had married into the Bunton family. So he mined that too, as all good politicians do. Most of these are before my time, but his congressional career started in ’37.

So I cut my teeth with his first election for the Senate, which he—thereafter the war and the big Coke Stevenson fight. Most of the people here were loyal to him although there was an anti-Lyndon faction that—I’m sure you’ve talked with the Henry Kyle family or you will.

THIBODEAUX: No, not yet.

BARTON: Not yet, but I hope you do. I mean, Henry’s no longer around, but there were others that went to the—hard feelings there had developed over campus politics, I think, at Texas State. But there were a number of families here fell out with him over parochial or local interest here in Kyle. Hearing about it later after I came here and went into business more than fifty years ago back in the newspaper business—and I’ve been in and out—but it was strong Lyndon Johnson country during certainly the ‘30s and the ‘40s. He carried it in his early—his reelection bids and then did quite well in his Senate career when he first ran for the Senate.

Then later I graduated from high school in Buda in ’47. You know, he sent letters to every graduate in his whole district. In that sort of constituent services he was quite, quite good at. But I never had a personal relationship with him. A good bit of age difference, and my moving into the present in 1956 at the first—I was an active populistic maybe liberal democrat, so even by the time he’d gotten in the Senate, I wasn’t always with him on issues. I was—he tended to be more conservative—in my youth was an anti-—but he was nominated by oil interests and big business interests, and I have great admiration for what he did, of course, as far as the civil rights bills of the ‘90s [60s]. I ended up being an opponent of the war with Vietnam, and so there were some periods of alienation—of some alienation in some of those periods. But he had great, great skills.

I was mentioning back in the early ‘50s. As a very young man the first state democratic convention I went to there was a fight. And it sounds very parochial now between the—I tended to be a Ralph Yarborough democrat, which was the most liberal wing of the Democratic Party, so we did not always get along. But I was very friendly with the Johnson people, so the first convention I went to—state convention in ’56 when Lyndon was a favorite son but not really given much chance of winning.

But the state convention divided. We had had a big fight between the forces of Governor Shivers and Lyndon Johnson, and by that time Ralph Yarborough had been elected to the United States Senate. So when Yarborough and Johnson didn’t always get along, but Sam Rayburn got them altogether. So there were loyalist democrats and there were Shiver democrats. So I got elected, I believe, as an alternate that year among Judge Will Burnett and Ernest Morgan and a number of Lyndon loyalists. We had a very—again, sounds very parochial now—a big fight between who would be national committeewoman from Texas and many of Johnson’s closest supporters in San Marcos. Judge Burnett and Ernest Morgan and others that were there, Yancey Yarborough, all were delegates. And some of us—I was in my mid-twenties—were alternates, and we sat up in the balcony. But they got into this big fight over who would be national committeewoman, and the most liberal of the committeewomen that Johnson—a woman called Frankie Randolph was running. Lyndon was trying to stop her being elected even though we’d all sided together earlier to support him for favorite son.

On that, they split into factions. It was so close that he started calling in individual delegations to lean on his people that were torn both ways. San Marcos was particularly torn because the leader for Mrs. Randolph from Houston was a prominent San Marcos man. Now I can’t call Smith’s…

THIBODEAUX: J. Edwin?

BARTON: J. Edwin Smith. J. Edwin Smith was the campaign manager for Mrs. Randolph. So some of these men were terribly torn because they were good friends—some of them had gone to school with both Lyndon and Smith. So their solution late in the day was one by one they would call those of us who were alternates and say, “We’re going home. We promised J. Edwin we’d support his candidates, but Lyndon will call us in and lean on us and call up old friendships. It’s just too hard. We’re going home and you all are delegates.” So you need to talk to Al Lowman. You maybe have already talked to him. (laughs) He and a guy named Henry Armbrister in Buda, who’s now a very ultraconservative but he would remember this. I remember the three of us replacing Judge Burnett, who wasn’t scared of the devil or anybody else, but he didn’t want to—and replaced two or three of them. So the one chance I had to have a one-on-one relationship with Lyndon, we went off and hid to keep from having to—or made ourselves scarce. (Thibodeaux laughs) So that’s the way I remember it. They may disagree. At least I can speak for myself, so none of us went. We had the moral—at least I didn’t—to be able to withstand his arm around you and leaning on you a little bit.

Then when he ascended to the presidency in the election of ’64, I was living in Austin but had a business in San Marcos, so we had a spirited campaign, and I was not deeply involved in the organization of the county for him. But we had a guy named Bill Malone, who’s an ex-professor there, had just come to San Marcos, a historian, who now lives in Minnesota and is retired and had taught at other schools later on. He and a guy named Charles Chandler, who I believe was a sociology prof. there, had written a song that we had a lot of fun with called “His Name is Lyndon, but it’s not Andrew Johnson,” which was funny and humorous and they sang it at rallies.

So in the ’64 election and even after he was elected in his own right, there was a large element of us in San—I mean, a small element perhaps—more liberal people who were with him on his civil rights and much of his legislation, but were frowned upon still by the—we were still sort of a one-party state. And the republicans were very, very weak at that time. So we had, in my viewpoint and others’ viewpoint, the majority of the people in the Democratic Party really weren’t democrats. So we had that strife.

So I remember the convention probably of ’66 before we’d gotten deep in the war, where the county democratic convention was dominated by Lyndon loyalists, but those of us who were too liberal were basically in the minority. Even though in the big library box in San Marcos, I remember having a roomful of people. We were in the—progressive liberals or whatever they were called were in the minority. And we introduced a string of resolutions, all of them backing things that Lyndon was supportive of, but his older friends, more conservative friends, established friends, started the business establishment, voted against every one of those, and then they voted to endorse Lyndon and sent people pledged to Lyndon. As I recall, maybe Dr. Bill Pool, who was a progressive liberal supporter and had a little more prominence and perhaps was on the city council at the time, I think they chose him as the one token liberal to be on the delegation to the state convention that year.

But he did some wonderful things. I was in business, ran the Colloquium Bookstore for twenty-five years and was certainly active in the business and political. But I was at that time considered a renegade—you know, I became sort of a member of the majority as we divided into two parties. But so I really had no particular—other than being in the crowd when he frequently came there to speak. When he announced—introduced his legislation in San Marcos in the assembly to create the Job Corps was a neat time. So I have positive memories of him and reflecting backward thirty years, there was a lot more good to him than bad. And he cared about poor people. He made compromises, as all politicians do, as a young man to get where he’d gotten. He probably wouldn’t have gotten there if he had not. (laughs)

I’ve just been reading some recollections of someone that had worked for Sam Rayburn, whom I did admire, who’d always been a little bit more—he represented a district that he could afford to be more liberal than perhaps Lyndon could. I make excuses for him. (Thibodeaux laughs) At some of those times, I actually was so anti-war that it was not a very—I worked for a guy named Fagan Dickson, who ran against Jake Pickle in ’68 right before Lyndon was going to run and then withdrew. This Fagan Dickson, who lived and was an Austin lawyer and had been old liberal warhorse. I’d gone and volunteered and worked the rural counties for him in his congressional race, and he ran on a platform and had signs up, “Bring Lyndon Home,” as a protest against the war. Of course, then Lyndon withdrew and Fagan quit his campaign, but was still on the ballot. It was not a very friendly reception in San Marcos or Georgetown or any of the towns because Lyndon was much loved by people that cared about him. So there was sort of a third group of us in fairly small minorities that certainly weren’t republicans were more on the war.

Of course, then it happened on campus too. There was marches and that sort of thing against the war. That’s pretty much my story, and I’m sticking it with. (Both laugh) But I’ll be glad to answer any questions or whatever.

THIBODEAUX: Well then, I think I’ll back up, but I do want to get back to the war protest in just a little bit because—

BARTON: Okay.

THIBODEAUX: —there seems to be amnesia among many people when it comes to that.

BARTON: Yes, they are. I’m old and can be more honest than some. Maybe I’m no more honest. I’m jaundiced in my viewpoints, of course.

THIBODEAUX: (laughs) I did read in a recent article that you mentioned that you had just some memories of what life was like before rural electrification.

BARTON: Yeah. It’s one of the reasons people loved Lyndon here regardless of his politics. Because I do think—and I was a child, I mean, seven or eight, when the rural—we had—I lived in downtown Buda and we had electricity. I moved to the country during the war and we didn’t have—the house we moved into didn’t have electricity, and things were frozen. So I lived several years with lamps when I was a teenager. So I even—but the vast difference it made. It was enormous, and he is due a great—I mean, there were other people working on it, but he capitalized on the movement and had the strength and the ability to—the tremendous ability—to lean on people and to manipulate people. When I mentioned his charm and his energy was so great, that at the age of twenty-six when I had a chance to visit with him, I didn’t want to visit with him because I was pretty confident that if he leaned on me, I’d end up voting the way he wanted to.

But back to the electricity, it was an enormous—he was a New Dealer in that campaign he ran. President Roosevelt endorsed him and he ran for packing the court. I was too young with that and he might’ve been more liberal than I was at the same place in life.

And all sorts of people loved him, and they still loved him when he became—I think he predicted that his action on the civil rights bill would lose the South for the democrats for many years to come, and it proved to be true. So it was an act of courage, and I think—their family was—if you read—they were genteel poor is what they were. His mother well-educated, but they lived just above the poverty line, and I think apparently—I’ve read a lot about his father was kind of a ne’er do well, a good politician, was a popular man, but had a hard time making a living. It’s a very—that first [Robert] Caro book about how fragile—we’re on the edge of the desert, and more bad times through the years than good. My family’s been in the agriculture or ranching business here since, well, maybe in the early years. My great-great-grandfather came as a Mexican land grant, and he was probably a land speculator. But very quickly they tried to make a living out of agriculture and some years did quite well and were by rural standards modestly well off, but by the standards of the Census Bureau would be somewhere in the middle class or down a step or two most of those years.

And the Johnsons were just like that except they were that political—I mean, both his grandfather and his father, I think, were political animals and popular perhaps in practical. I once told—I’d read his grandfather when he ran for the legislature as a populist, it was the—Grover Cleveland was president. And I had found this little tidbit of information in one of the old San Marcos papers that was anti-populist—so it may not have been true—quoting Lyndon’s grandfather as saying in some speech—and they used it against him—that somebody ought to shoot Grover Cleveland. Well, I made the mistake of telling Luci—trying to tell Lynda, I guess—she and Chuck [Robb] had some gathering—just in some causal moment about—I was bragging on him for being a populist. And she looked at me like, you know, what—I’m sure she thought I was demeaning the family and I was trying to say I had admiration for him ever since his—and then I may have said something like, you know, “I wish Lyndon’d been more like his grandfather.” But I may have said that at the time, I don’t—or I probably felt that at times. But anyway, history is going to prove him to be like most people, flawed in some ways but had greatness about him and did some wonderful courageous things.

THIBODEAUX: The elections between—because he was congressman for, like, about eleven years—

BARTON: Right.

THIBODEAUX: —and then senator for a while. Did he ever have any competition during those years?

BARTON: Yeah. Of course, that first election, which I don’t remember but I’ve read about it, he ran with the support of the New Dealers here at a time where a New Dealer was very, very popular. I don’t mean this in a bad way, but he was a smart man and he assessed the situation to being 100 percent Franklin Roosevelt man in 1937 was not a dumb thing to do. And a number of the candidates against him really would’ve been republicans if there’d been a Republican Party. There was a very small Republican Party, and they wanted to keep that way because mainly it was the way you got in line to be a postmaster, you know. I don’t think he had—perhaps in his second reelection, but as congressman, I mean, he dominated the scene. He never had a serious opponent after that first election, I don’t believe.

Then the Coke Stevenson race, which I was a teenager then and in high school, in this area he was still extremely popular. I haven’t looked recently. I’m sure he carried Hays County. He carried it all the way. Goldwater got, I don’t know, 35 percent of the vote or something. So there was unanimity among the business community and among—because of the burial of the young man that got—the Hispanic that got killed and then Johnson intervened, and because of his experiences as a schoolteacher in—what—Cotulla, I believe. He always had strong support within the minorities. The minority community didn’t vote in very large number, nor were they encouraged to vote by the people that were Lyndon supporters. I mean, he probably evaluated it. He was as liberal as he could be and be a senator. I’m critical of him—parts of me are critical of him for taking that attitude, but then he wouldn’t have done a lot of good—if he hadn’t been there, he wouldn’t have done the good things that he did.

THIBODEAUX: So you started at Southwest Texas State Teachers College—

BARTON: I did.

THIBODEAUX: —in 1950.

BARTON: No. I actually went there in the fall of—I was still seventeen years old. I went to college for a year and commuted and then went—in the Berlin Crisis I went into experimental universal military training at eighteen for a year. Then when the Korean War broke out, I’d been back in school a year, so it took me six years—I went to the army twice. I volunteered in the Korean War and went back for a little over a year. So I was there—I finally graduated in January of ’54, I believe, or something.

THIBODEAUX: So what was, I guess, the political landscape of San Marcos like?

BARTON: I worked on a couple of out-of-state newspapers, and I came back and went into the—my father-in-law was a local merchant here in Kyle and then he also was a Ford tractor dealer. So we bought—I was working out-of-state on a newspaper, and he bought the Ford tractor dealership in Austin, so I moved to Austin for three or four years, but I really wanted to come back to Hays County. So we founded Colloquium Bookstore there in ’63. So I came back in spirit for a year or two in actuality but lived in Austin for a year or two. So I came back to San Marcos.

And it was quite a different town. It was full of second-class citizens including the students. So I was fairly deeply involved in city politics in the late ‘60s and mainly the early ‘70s or most of the ‘70s, where we used some of the idealism of Lyndon. I mean, that wasn’t the spark of it, but people that, as I said earlier, that we had a rebellion within the community of uniting Hispanics, which was the largest group. Not many African Americans, lots of students, but a great divergent of—they wanted to talk about the war. The police for a period of time treated them somewhat as second-class citizens. It was not an easy thing to build a coalition between students and culturally conservative Hispanics on cultural issues, except the war and the antipoverty program that Lyndon, of course, had started, and all the work that a lot—the emergence of a lot of Hispanic and smaller numbers because they were a smaller community of African Americans and some student leaders. So it were some fun—I don’t know if fun’s a good word—but an interesting and exciting time. And I was somewhat insulated from the one I have—my mother’s side, my uncle had been a president of the old Coronal College [Methodist College in San Marcos from the 1870s to about 1920], and her grandfather had been the Methodist preacher. So I was sort of old family removed by a good many years in San Marcos and because I wasn’t a BISM, I wasn’t born in San Marcos, but I was a BIHC, born in Hays County, so made some excuses among some people for the fact that I was on the wrong side politically at least with some really good people in San Marcos. Most of that through the years, you know, dissipated considerably.

THIBODEAUX: I’ve always heard that on campus it was still pretty conservative, pretty mild. Was there a bigger antiwar movement in San Marcos?

BARTON: We had two things. We had the antiwar movement and the anti—

THIBODEAUX: McCrocklin?

BARTON: —President McCrocklin got in trouble over, and I was fairly deeply involved in that because I had friends. Most of the profs. that exposed that or revealed that or whatever you want to say, it was backed up later by UT. And those were not—I mean, there were a lot of good people on both sides, but that. But the antiwar—we had lots of marches and lots of—and I was in a—I went to bond for people on—I, myself, was and am anti-drug, but I was not unfriendly to people that got picked up for marijuana or something.

And I operate a business that economically was not dependent on the goodwill of my fellow Anglo merchants. Some of them I was unfriendly with and they were unfriendly with me, but I was insulated somewhat because I was dealing—that was where my natural inclinations were, but it was nice not to have the pressure of—

One of my acquaintances—and now really friends—in some bitter argument—and I’m not going to mention his name because we’ve long since healed the breach—but he was also in business in San Marcos. In this argument he in a moment of heat said, “You’re so wrong and you’ve done so many bad things that I’m going to organize a boycott of your business,” and I think then he went home and thought about it for a while. And he was in a business that dealt with students, and so he called me the next morning early and said, “Let’s have breakfast together.” He said, “I was just hotheaded and I don’t want to start—and please don’t try to organize one against me,” which I don’t think I would’ve done, I didn’t do and we became—

So there was great fear. When students were given the right to vote, some people in town thought San Marcos was going to hell in a hand-basket. Of course, I was very much for—we found out in the 1972 election when Richard Nixon ran, that most of the students voted the way their parents did.

THIBODEAUX: Yeah.

BARTON: And those of us that were for the democratic candidates in those years got wiped out. We were in the vast—it wasn’t much better with Stevenson. There was some in internal city politics—there was, I think, a progressive spirit that developed. Then even that is—those old divisions no longer exist. New ones exist, and I’ve lived back down here where I grew up for the last twenty years, so I’m not intimately involved with that, but there was.

And the antiwar thing was a—it did develop. The bond that—it was one of the bonds and it worked out that the police got better. I mean, there was a period of time where long-haired students were harassed, and there were people that didn’t want students—didn’t want people to vote at eighteen. Of course, we also had a period of time where you could drink at eighteen too, which was a big economic thing. I think most people—I’m sure I supported the right to it. I’m not upset by it being twenty-one again.

THIBODEAUX: That brings to me a question. I’ve read that there was a cross-burning in your yard.

BARTON: Okay. There was. You’ve done a lot of reading. Yeah, there was. During the—I can’t remember whether it was in the McCrocklin days or the—it was more of local politics than anything, I think. I was one of the principal Anglos in that coalition, which numerically was more student. There were what people called then the liberal element. That’s profs. and others within the San Marcos community. This was after Martin Luther King being shot and Bobby Kennedy being shot. Of course, a little earlier of John Kennedy being shot. So there were strong feelings on both sides, and I was—in fact, Bill Crook’s—Elizabeth Crook told me—no, I believe she wrote in the article that she wrote about—I don’t know if you’ve read in Texas Monthly. In fact, you probably ought to talk to some of the Crook family. Have you?

THIBODEAUX: I did talk to Eleanor.